Why are the current policies for fighting against deforestation doomed to failure ?

Even if national and international efforts towards the fight against deforestation have multiplied in the last few years, nothing proves that those initiatives are working. That is what is asserted in an article recently published in One Earth (Cell Press). Co-ordinated by Claude Garcia of the Cirad and of the ETH Zurich, the international team behind this document calls for a radically new approach, which concentrates on the way in which we understand the individual choices relating to the management of forests and natural resources.

The call comes from a group of 23 researchers, consultants and NGO stakeholders in 13 European and North American countries. This document marks a first stage in their collaboration. Together, they assert that the policies for deforestation and reforestation must review the way in which they take account of human decisions and not their ambitions. For these specialists, the choices and the human activities that result from them are a blind spot in the policies and speeches about forest and landscape transition. The article insists on the necessity of making the stakes and the interests of the decision-makers, whoever they may be during the negotiations, explicit.

In this way the authors propose a wholly new approach: that of strategy games, which shed light on the objectives and constraints of the stakeholders in forest management. That method has, moreover, already proved its worth in several arenas of negotiations on local and regional levels. The games help the players to overcome prejudices and to find a way out of stalemates. The authors boldly suggest that the negotiators in the great international negotiations, such as the COP15 of the Convention on Biological Diversity (October 2020, Kunming, China) and the COP26 of the United Nations Conference on Climate Change (2021, Glasgow, United Kingdom), should join in the game! “We’ve been discussing this for a quarter-century and yet we’re far from having reversed the trends. It’s perhaps time to try something else,” declares Claude Garcia, ecologist with the Cirad and leading author of the article.

A track record of failures

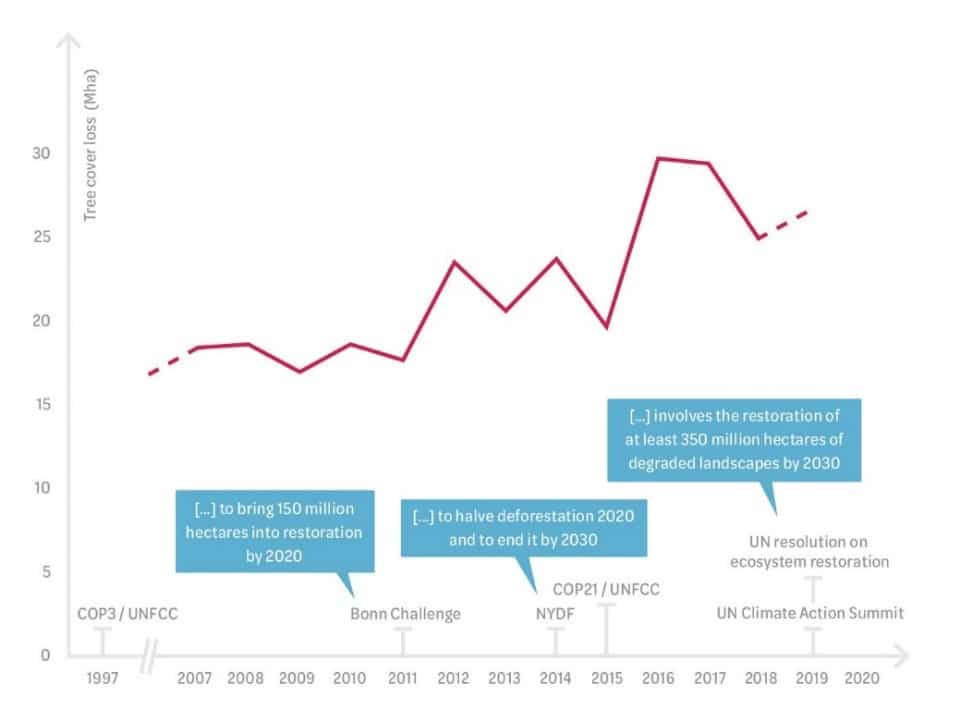

This article shows that despite the many national, international, public and business initiatives of these last years, the objectives have not been reached and the trend towards deforestation is continuing, or even starting to rise again, if degradation is taken into account. In its report on the state of the world’s forests [1], the FAO estimates the average number of hectares of forest lost annually over the decade to be 11 million, which is lower than the 15 million hectares lost per year in the preceding decade. “But that estimate does not take account of natural damage and forest fires,” underlines Claude Garcia. Yet in 2015 alone, according to the same report, forest fires affected 4 % of the world’s tropical forests, mainly in Africa and Latin America [2]. “And even if, in Australia, the causes of the fires are mostly natural, that is not the case in Brazil, Colombia or Indonesia”.

In September 2019, the companies Nestlé and Procter & Gamble announced that they would not reach the zero deforestation objective that they had set themselves. Entire countries, even, make mistakes: ten per cent of the signatories to the Bonn Challenge set themselves the impossible objective of restoring a forest area which, in terms of surface area, considerably exceeds the area for restoration available even within their own borders [3]. More recently, Brazil has seen an upsurge in deforestation at a time when the Covid-19 epidemic has been raging throughout the world.

For the authors, the determining factor in all these situations remains the way in which humans take decisions. “Successes here and there don’t register on a global scale, and at best they tell the tale of battles won but a war that’s being lost”, writes the team of specialists, who have entitled their article, “The global forest transition is a human affair”.

Despite all the national and international initiatives, deforestation on a global scale is not slowing down. (Data taken from Global Forest Watch).

Landscapes of values and standards

In order to better understand why the policies are failing, the group considers that it is first essential to understand the human choices and actions involved in forest transitions [4], as well as the “mental models” of the stakeholders, that is to say, the way in which individuals see the world and take decisions. Until now, that part of the puzzle has been largely neglected, which could explain why the negotiations end in stalemates and the commitments and policies turn out to be ineffective.

Sini Savilaakso, visiting researcher at the University of Helsinki and principal co-author of the document, says, “Instead of imposing objectives and proposing visions that are not shared, let’s rather start to build together”. In the opinion of the team of specialists, we should abandon the hypothesis according to which everyone must work to achieve a common objective. To the contrary, they propose a method that enables the stakeholders and the decision-makers to “align their strengths”, despite values and perceptions of the world that are different or even opposed. Seen thus, the specially-designed role games can prove to be essential tools in the process of introspection, learning and negotiation.

Playing the Anthropocene game

Thanks to the games, the participants can become aware of their perspectives and their decision-making processes, which enables the identification of compatible objectives. The games offer the participants, playing their own role or someone else’s, the chance to live out the experience of decision-making and its hypothetical consequences, thus making the lessons learned more meaningful. The method was particularly successful in 2018 when, after two years of deadlock, a game of this type enabled the participants to come to an agreement on the management of the intact forest landscapes in the Congo basin (see the box).

“Rather than blindly trusting artificial intelligence to identify the decisions that we should take, we prefer to bank on collective intelligence”, declares Claude Garcia about this innovative and yet hardly technological method. “It’s a very anthropocentric approach”, he recognises. “But after all, we live in the Anthropocene”.

A game to manage the intact forests in Central Africa

It was in Brazzaville in 2017 that the experts invited by the Forest Stewardship Council used a game to break the deadlock in the negotiations, which had lasted for two years. The issue in the negotiation was the definition of indicators and management rules for the intact forests in the FSC-certified concessions in the region. The MineSet game enabled the government representatives, the local populations and the indigenous peoples, the certified businesses and the conservation NGOs, to understand each other better and to find an agreement in only three days, whereas the situation had seemed definitively deadlocked. Designed by the stakeholders in the field with the help of scientists from the CoForSet project, and financed by the FFEM (the French Facility for Global Environment) and the FRB (the Foundation for Biodiversity Research), this game represents, over 10 years and on a regional scale, the interactions between ecological processes, individual strategies, and external factors such as demography, changes in governance, and the fluctuations of the international market. “If the method has worked, that’s because it has put the decision-makers in a position to create strategies that are wins for everyone there, whereas before there were only divergent interests”, Claude Garcia underlines.

References

Garcia et al. (2020) The global forest transition as a human affair. One Earth. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oneear.2020.05.002

[1] http://www.fao.org/state-of-forests/fr/

[2] FAO. 2020. Global Forest Resources Assessment 2020 – Key findings. Rome. https://doi.org/10.4060/ca8753en

[3] Bastin, Jean-Francois, et al. « The global tree restoration potential. » Science 365.6448 (2019): 76-79. https://science.sciencemag.org/content/365/6448/76

[4] The term “forest transition” refers to the change, on a regional scale, of a shrinking forest area into an expanding forest area.

To find out more

Further reading

https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2019/05/could-games-solve-the-worlds-deforestation-crisis/

https://news.mongabay.com/2017/10/supporting-conservation-by-playing-a-game-seriously-commentary/

Contact :

Dakota Communication

01 55 32 10 40

info@dakota.fr

Scientist

Fabien Quétier